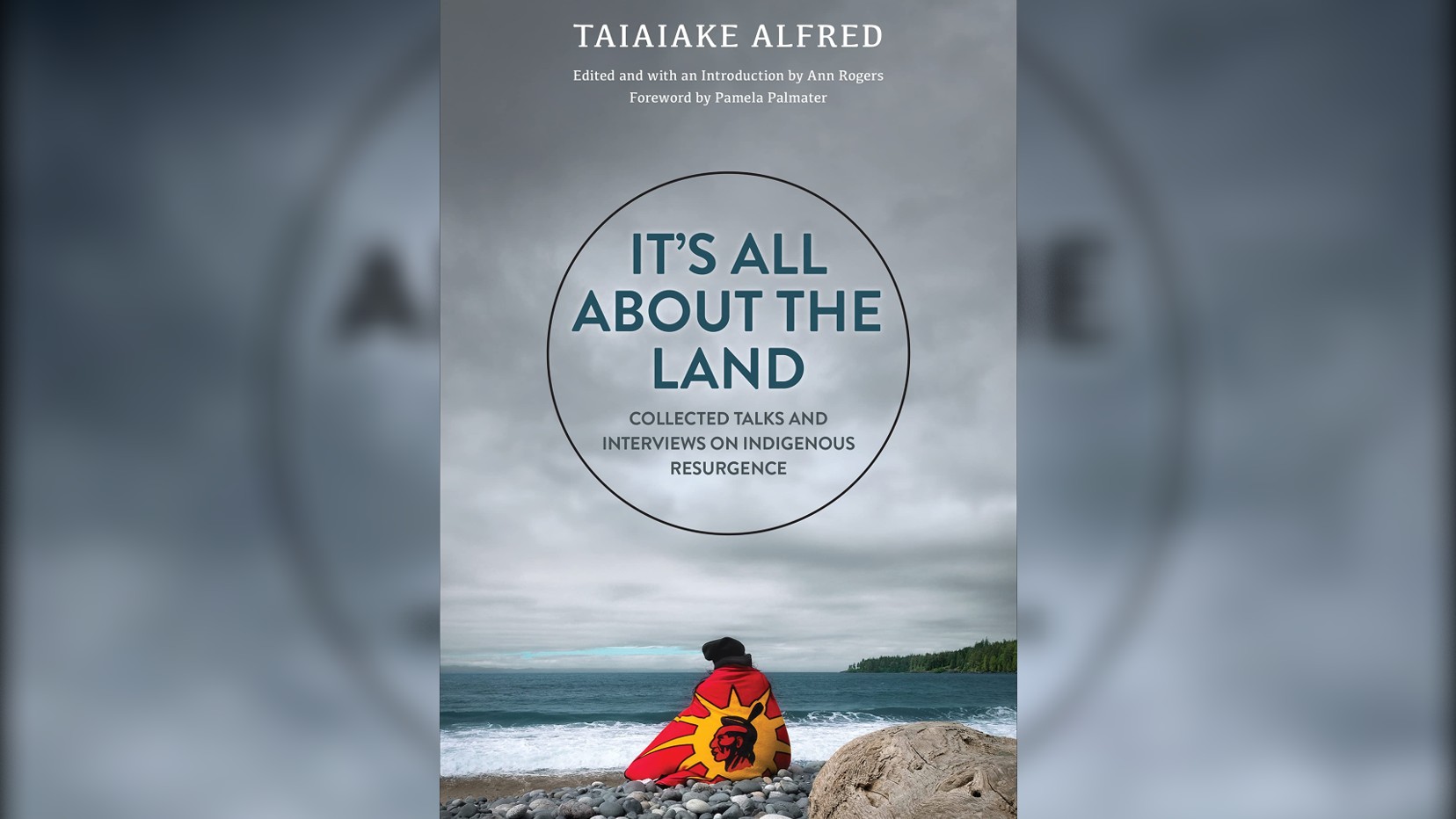

Taiaiake Alfred guides us through the history and importance of the revitalisation of Canada’s First Nations culture and identities

What forms has the dispossession of First Nations in North America taken throughout history?

The relationship between the Original People of this continent and the newcomers has been shaped from the start by Europeans’ and later Euroamericans’ insatiable greed for our land and their unceasing efforts to gain possession of our resources and to erase us politically. We have always been an obstacle to European ambitions and demonised in colonial mythology. Our peoples’ struggle has been to maintain ourselves, to survive the violence and legal machinations of the White Man in our homelands. The first stage of this history was defined by treaty making on a nation-to-nation basis, which was a necessity on the part of Europeans because of our numerical superiority. But as soon as the impacts of epidemics of disease took their toll on our people, and reduced our numbers drastically, North American history became a story of broken promises, naked aggression, legal fiction and forced acculturation with the aim of eliminating First Nations as obstacles to the expansion of Empire. The forms of dispossession included disregard and legal reinterpretation of treaty commitments, outlawing of First Nations’ rights, governmental supports for outright theft by White settlers, physical removals of communities and nations and later, forced removal of generations of First Nations children from their families and communities and placement in so-called residential schools run by churches with the intent of deculturing them and assimilating them into mainstream society.

In what ways have First Nations historically resisted land and cultural dispossession?

When Europeans first set foot in North America there were around 500 nations of people occupying the continent – distinct linguistic, cultural and political collectivities. Now there are only around 50; the vast majority of the original people of North America were wiped out by diseases brought by Europeans and by war. The ways First Nations have resisted include the obvious, military force from the start through to the 19th century – and this is not an historical fact only, because as late as 1990 there was a sustained armed conflict between the armed forces of Canada and my own nation. But beyond physical resistance, First Nations have organised and advocated in the courts for their rights since the 1970s and this has been effective in preserving the bare essence of the reality of a treaty-based nation-to-nation relationship between First Nations and Canada and the United States governments. In recent decades, as our existence has felt less threatened than in previous eras, our people have turned to restoring and revitalising our cultures, focusing on reinvigorating our languages and ceremonies and land-based cultural practices.

What was the impact of the attempted “assimilation” of First Nations’ people in North America?

First Nations people have been severely impacted physically and psychologically. In all First Nations, the impacts of the multi-generational trauma of colonialism and Settler racism are profound and manifest in many ways. Our people, sadly, have social pathology, incarceration, and disease rates, just to name three measures for example, that far outpace the mainstream population and affect every one of our families. But most profoundly, the multi-pronged assault on our people over generations has created a social reality in our communities that could be best understood in a Fanonian sense of a colonised mentality – it has disconnected our people from the source of their identity – their lands – and fomented divisions, cultural confusion and undermined people’s trust in themselves and their Indigenous institutions.

Over the last few generations, how have First Nations people been reclaiming their heritage and revitalising their identities and cultures?

It’s been a monumental effort on the part of our people to simply survive the Euroamerican governments’ attempt to eliminate us. Those of us that are still here are the inheritors of a heritage of resistance and courageous, wise choices on the part of our ancestors. We are the survivors of a genocide and while this history has scarred us, it has also made us resilient. Our ancestors knew that aside from fighting like hell, not trusting the White Man and not allowing one more inch of our lands to be stolen by force, decree or fraud, preserving our identities and connections to our homelands was the key to survival and ensuring that our future generations would know themselves and live as Onkwehonwe, original people, and the key to this was the preservation of our languages and spirituality. We have adapted many forms of technology to restore languages, and expanded the ways we practise and share our culture in recent years, especially in the arts and contemporary forms of music.

Why is the Indigenous Resurgence movement important to First Nations?

I think that framing our resistance as Indigenous Resurgence, which is an idea that focuses on the restoration and adaptation of ancestral identities and practices and direct action to get our land back, is the key to our survival in the long term. We cannot exist into the future without a meaningful connection to the unique heritage that defines us as nations and without a real relationship to the natural world and the landscapes and sacred places that are essential to our being Onkwehonwe and the birthright of our future generations. The idea of Indigenous Resurgence, as an intellectual paradigm and political movement, reflects and strategizes these imperatives. It’s the only effective alternative to assimilation and integration into the agenda of the North American states.

Subscribe to All About History now for amazing savings!